Upcoming Endometriosis Awareness Events:

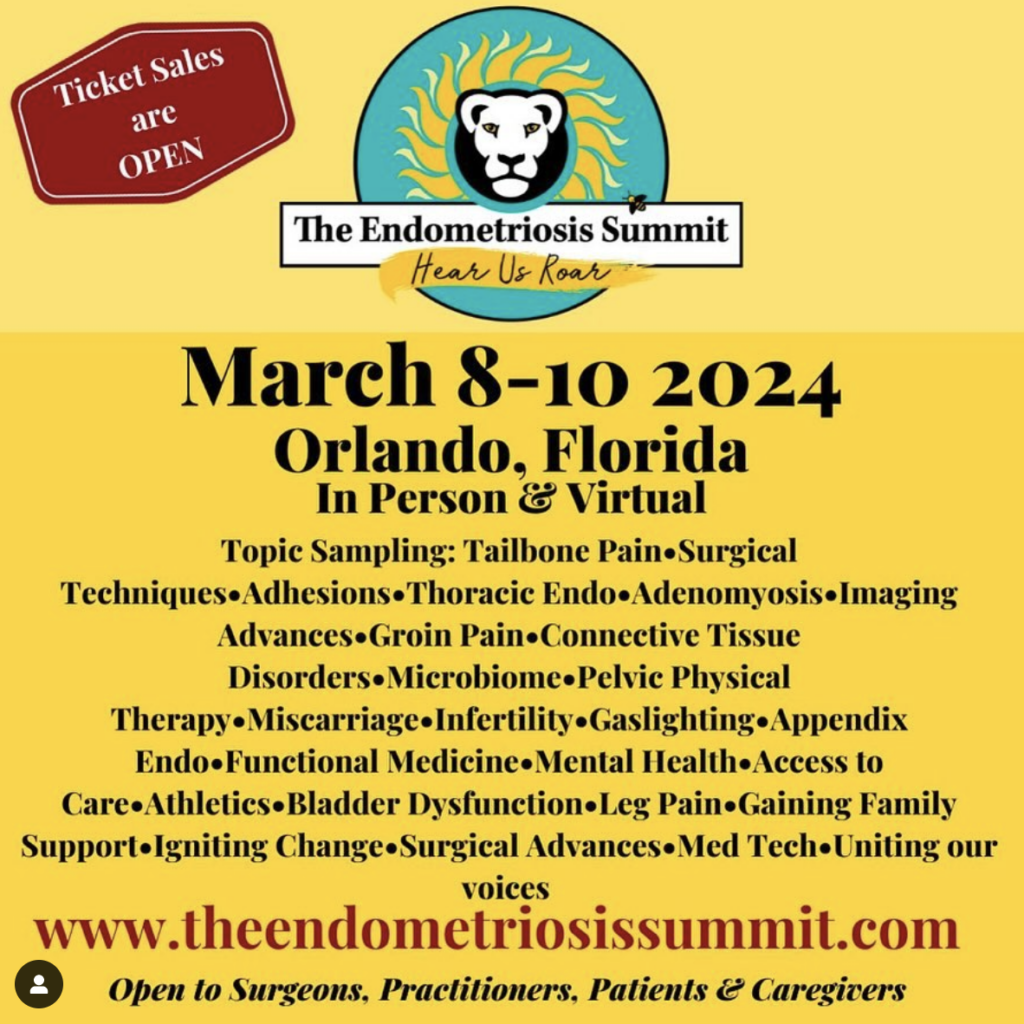

March 8-10, 2024

Endometriosis Summit

https://theendometriosissummit.com/

March 16-17, 2024

Endo Black Conference

https://www.endoblack.org/events

March 23-24, 2024

Virtual Endometriosis Conference

(Worldwide Endo March)

https://nezhat.org/save-the-date-virtual-endometriosis-conference-2024/