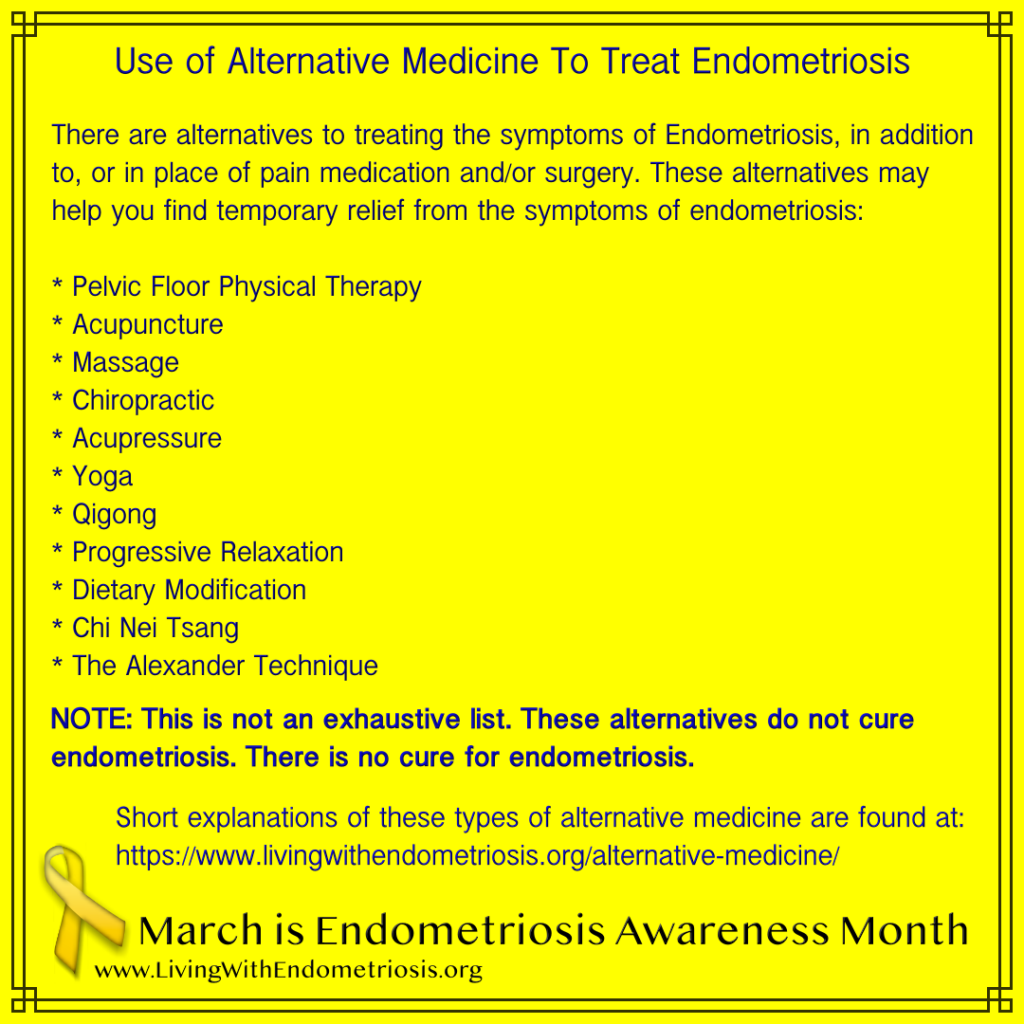

Use of Alternative Medicine To Treat Endometriosis

There are alternatives to treating the symptoms of Endometriosis, in addition to, or in place of, pain medication and/or surgery. These alternatives may help you find temporary relief from the symptoms of endometriosis:

- Pelvic Floor Physical Therapy

- Acupuncture

- Massage

- Chiropractic

- Acupressure

- Yoga

- Qigong

- Progressive Relaxation

- Dietary Modification

- Chi Nei Tsang

- The Alexander Technique

NOTE: This is not an exhaustive list. These alternatives do not cure endometriosis. There is no cure for endometriosis.

Short explanations of these types of alternative medicine are found at:

https://www.livingwithendometriosis.org/alternative-medicine/